Sylvia Vong’s Not a token! A discussion on racial capitalism and its impact on academic librarians and libraries is such an important piece in the LIS and CRT literature. This piece hits home for me what is racial capitalism: the commodification of the performance of one’s racialized identity in specific settings identified by the dominant group. Many years ago, I remember attending an interview when a candidate named dropped a bunch of EDI initiatives, including my name, during an interview. Not only was it the first time I came across pure strategic performativity at an interview, but it also helped me understand now that I have the tools, to see it for what it was:

Racial capitalism places value on racialized librarians or staff members’ cultural knowledge when there is some capitalistic benefit (e.g. appearing multicultural).

- Fractured identities - The alienation of racial identity in the sense that identity may be bought and sold like in a marketplace. Racialized persons can never be themselves in the workplace simply due to the schizophrenic identities they need to assume.

- Racialized tasks - This is the work minorities do that is associated with their position in the organizational hierarchy and reinforces Whites’ position of power within the workplace. The UL's assistant once came to me asking to translate a passage into Chinese. While I didn't say I couldn't do it (I refused in the end), it was a reminder that regardless of my position or my CV, I'd forever be the other librarian.

- Identity Performance demands - The identity performances of racialized people that stem from pressures to perform their non-whiteness and to perform it in a way palatable to the white majority. I’ve seen so many racialized colleagues anxious and nervous to change the way they behave or whom they associate within group settings (sometimes even avoiding sitting with other racialized colleagues) as a way to fit in and “feel” included.

- Consuming trauma stories - This happens when the majority revels in listening (sometimes with empathy) to the difficult experiences of their racialized colleagues. This group consumption of racial trauma stories, unfortunately, results in further damage on racialized staff who must re-visit traumatic experiences in the presence of those who may have perpetrated acts of racism and discrimination. I have a close friend/colleague who loves sharing racist incidents in the news but bless their heart, have no idea how meaningless and hollow it truly is.

- Cultural performance demands - Outreach programming and events aimed at racialized groups for holidays or educating the larger community through awareness campaigns are often delegated or assigned to racialized librarians, adding more work and pressures to perform identity work. When racialized librarians are asked to perform identity work, they are tasked with cultural education or anti-racism and EDI.

- Cultural Taxation – The added time and workload of taking on anti-racism and EDI work are typically not financially compensated, meaning that most racialized people take on research, practice, and/or service along with EDI and anti-racism responsibilities in institutions where there are few racialized staff. They are added to various committees, positions, and expected to mentor in addition to meeting the goals and objectives in their annual work plans, all without acknowledgment of the extra work. What a deal!

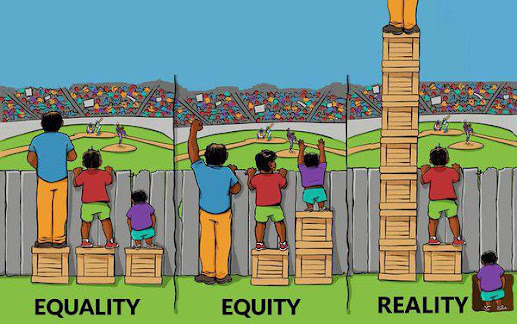

- “Conditional hospitality” - It’s the invisible workload that racialized people are expected to do, to give something back in return, on condition of being welcomed to the group. A lot of extra time and emotional labour goes into performing identity work, which adds to workloads that are typically uncompensated and expected from racialized library employees with the assumption that they are all willing and able to work on EDI and anti-racism initiatives and committees. We often hear the phrase by racialized pioneers, “I knew I had to work twice as hard to succeed.” That’s what we mean by being conditional.

- Pay inequity - Racial minorities are particularly vulnerable to broad fluctuations in market conditions, whether it’s the economy or the workplace. When there’s someone who is let go or comes second in a hiring decision, it’s often the racialized person. A disturbing study found that visible minority librarians in Canada earn substantially less than their non-visible counterparts.

It’s dangerous to assume neutrality in society, which is reflected in the workplace. In promotion and tenure/permanent status evaluations, procedures and policies may appear impartial, but decisions are often made by small groups of library administrators or elected colleagues. These evaluative processes are prime for bias and, although it can be argued that rubrics of evaluation help to restrict hidden prejudice, “they are typically constructed and draw on institutional and organizational goals and objectives that mould librarians into the image or vision of the organization.”

Vong offers words of encouragement as a way out: we need to introduce CRT in leadership and training as well as properly fund EDI work. This needs continued emphasis from leadership in organizations. Whether it’s a 400-person library or a three-person hospital library, change and inclusion require work that goes beyond tweaking tokenistic gestures.